The threat of invasion

After the fall of France in May 1940 it was widely expected that an invasion by the German army would take place later that year. It was decided that Britain should to be defended. Along with the whole of the south and east coasts, Norfolk was reviewed to assess its vulnerability. Deep water close to beaches at Weybourne and East Anglia’s relatively flat terrain leading across the industrial midlands were seen as enticing to the enemy. Norfolk had seen fixed defences built during the First World War and for hundreds of years had been seen as at risk from foreign invasion. Admiral Frederic Dreyer, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Home Forces in 1940, stated that Norwich Command must, “.…be prepared for an infantry attack on any portion of the coast”.

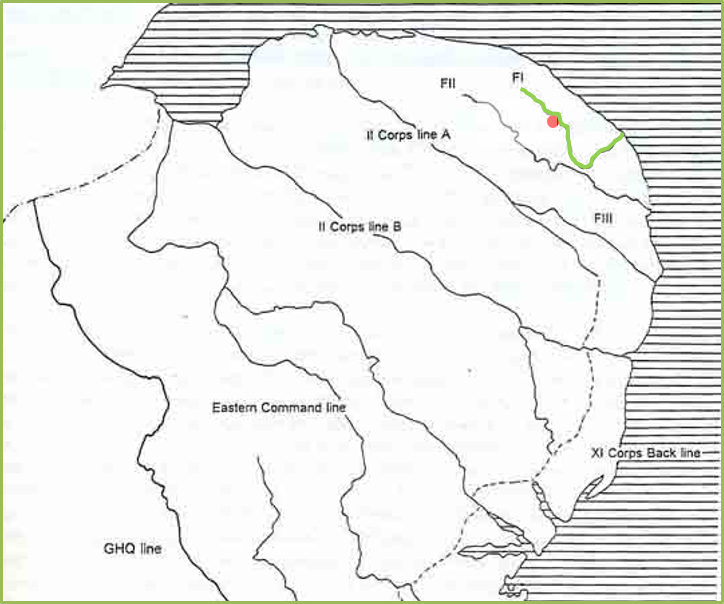

It was realised that a long coastline and the limited resources following the losses at Dunkirk meant that it was likely that an invasion force would soon overcome the coastal defences and be able to get off the beaches and advance inland. To avoid the risk of tanks racing across the county unchallenged, a series of ‘Stop-Lines’ were defined to hold up their advance and allow British reinforcements to be brought up. In total there were eight stop lines situated away from the coast all the way back to the Midlands.

These were placed to take advantage of pre-existing barriers to tanks such as rivers and canals; railway embankments and cuttings; thick woods; and other natural obstacles.

During May 1940 the Directorate of Fortifications and Works (FW3) at the War Office issued seven basic designs. During the summer of 1940 much construction by civilian and military forces took place around these ‘nodal points’ or ‘points of resistance’;

- Concrete pillboxes hexagonal in shape, of types 22 and 23. These were often next to their First World War counterparts, which in Norfolk had been mainly round in shape

- Concrete blocks called cubes or dragon’s teeth. These were designed to expose tanks and they frequently included loops at the top for the attachment of barbed wire

- Bridges and other key points were prepared for demolition at short notice by preparing chambers filled with explosives

- Trenches were also built so that troops could move from one bunker to another under cover and would also provide cover for men who were defending the line

- Roads offered the enemy fast routes to their objectives and consequently they were blocked at strategic points. Sockets were created in the road and on railway tracks, usually next to bridges. These were closed by covers when not in use, allowing traffic to pass normally but in the event of an invasion steel beams or rails would be placed in these to create roadblocks; ‘Hedgehogs’ of straight steel sections or ‘Hairpins’ of bent sections. Mines could also be placed across these defences.

Nodal points were designated ‘A’, ‘B’ or ‘C’ depending upon how long they were expected to hold out against enemy forces. Home Guard troops were largely responsible for the defence of nodal points and other centres of resistance such as towns and defended villages. Category ‘A’ nodal points and anti-tank islands usually had a garrison of regular troops. About 28,000 pillboxes and other hardened field fortifications were constructed in the United Kingdom that summer of which about 6,500 still survive.

North Walsham’s defences

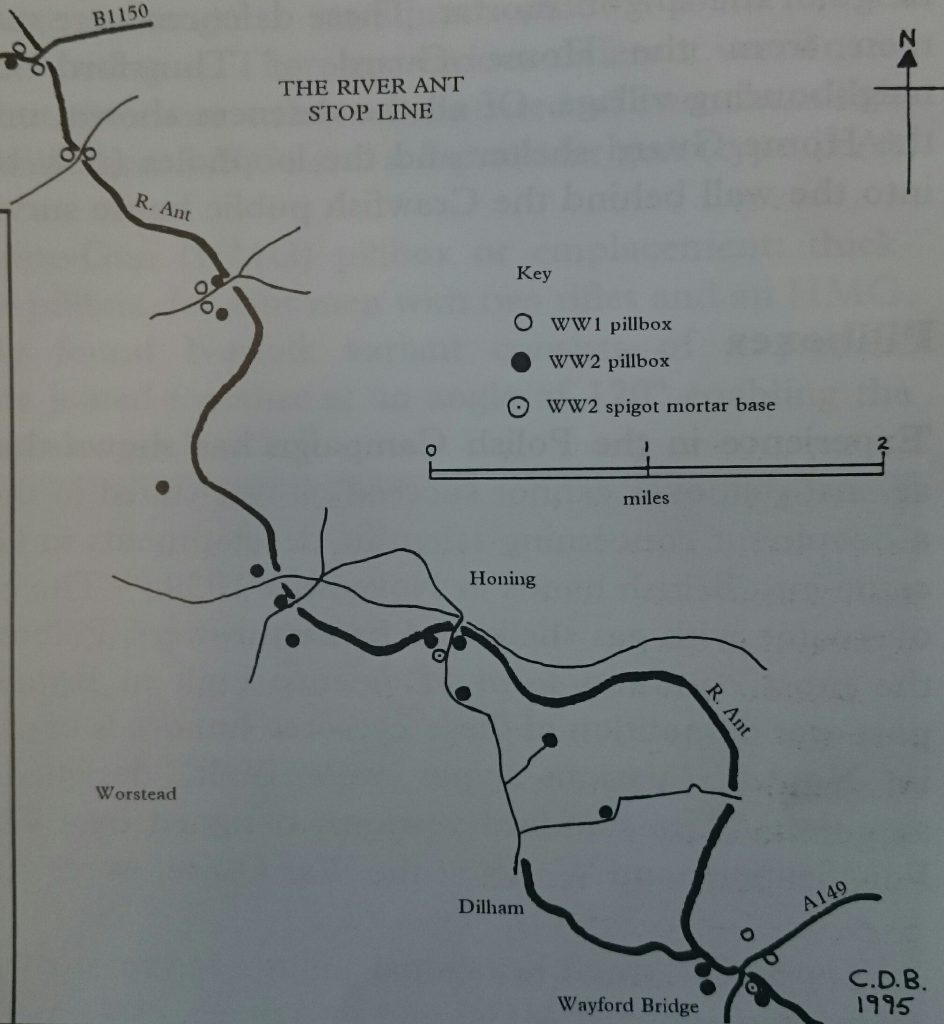

There were five successive lines of defence inland in Norfolk, based along the rivers Ant (Dilham and North Walsham Canal), Bure, Wensum, Yare and Ouse. North Norfolk’s first line of defence was the stop line known as ‘FI’, from Thorpe Market to Waxham, running along the North Walsham and Dilham Canal.

One of the best examples of how a stop-line Nodal-Point was formed near North Walsham can be seen on the Happisburgh Road. Here above the high ground that overlooks the canal and its bridge beside Ebridge Mill, can be seen two First World War circular pillboxes supported by a Second World War ‘Type 26’ and two ‘Type 22’ boxes.

At the bottom of the hill, next to the mill and close to the bridge a Hedgehog roadblock was built. Its shadowy outline can still be seen on the road on frosty days. The lock at Briggate Mill was mined for demolition and it is likely that the bridge and lock here were too.